Puberty Blockers Are Reversible. The Science Has Always Said So.

While new research confirms trans women have no athletic advantage, let us remember what puberty blockers actually do – and don’t do

This week, a major new study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine1 made headlines. Researchers analysed 52 studies involving nearly 6,500 people and found that transgender women do not have an inherent athletic advantage over cisgender women.

“Conclusion While transgender women exhibited higher lean mass than cisgender women, their physical fitness was comparable. Current evidence is mostly low certainty and has heterogenous quality but does not support theories of inherent athletic advantages for transgender women over cisgender.”

The Telegraph ran the story, the BMJ published the data, and the findings were clear: the current evidence does not justify blanket bans on trans women in sport.

That’s important. It really matters. It challenges the assumptions that have been used to exclude trans people from sport and from public life more broadly.

It also gives us a perfect moment to talk about something I’ve been saying for years, something the science has always supported: puberty blockers are fully reversible.

I spoke about this recently on LBC Radio2, and I want to repeat it here because it’s so important. The good thing is puberty blockers don’t have irreversible outcomes. They are completely reversible. If you stop a puberty blocker, your testicles and ovaries wake back up again and they start producing hormones.

That’s not my opinion. That’s the position of the Endocrine Society3 and the World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH)4. These are the leading medical bodies in this field, and their guidance is based on decades of peer-reviewed research.

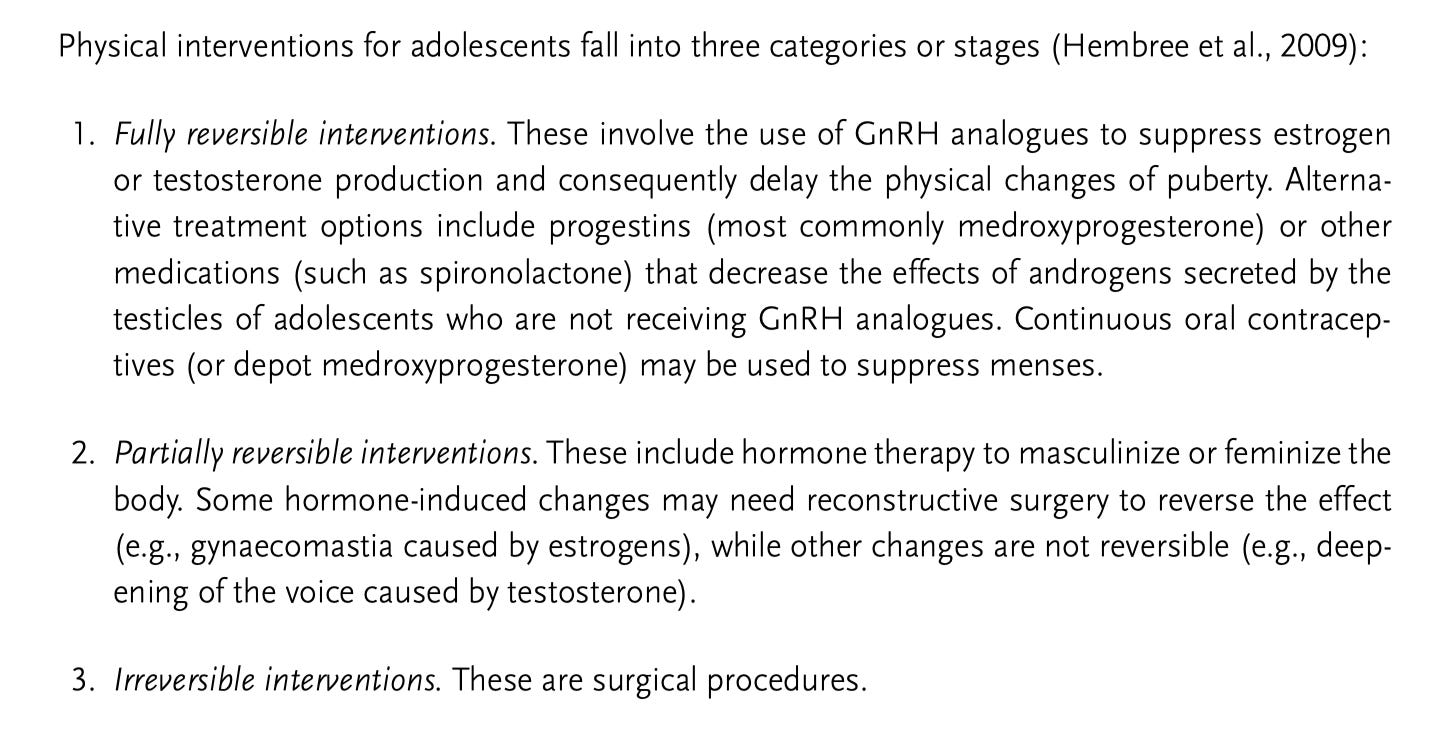

WPATH lays this out very clearly in a staged approach to treatment for adolescents. The first step is puberty blockers, which are classified as fully reversible. The second step is gender-affirming hormones, testosterone or oestrogen, which are partially reversible. Some changes, like voice deepening from testosterone, cannot be reversed, while others can. The third step is surgery, which is irreversible. Nobody disputes that.

This staged approach exists precisely because it is careful, measured, and evidence-based. Puberty blockers give young people time. They press pause on the physical changes of puberty so that a young person, their family, and their clinical team can make considered decisions without the added distress of watching their body change in ways that feel wrong.

When you look at the new BMJ sports study alongside the established guidance on puberty blockers, a very clear picture emerges. Trans women who have not gone through male puberty do not develop the physical characteristics that people worry about in sport. Puberty blockers prevent that from happening. They are the careful, reversible first step in a process that only becomes more permanent as it goes on, and only with informed consent at every stage.

So when politicians and commentators talk about puberty blockers as though they are dangerous and irreversible, they are simply wrong. The evidence says otherwise. The Endocrine Society says otherwise. WPATH says otherwise. The BMJ’s latest research adds even more weight to what we already know.

We need to listen to the science and stop letting fear drive the conversation. Young trans people deserve care that is based on evidence, not political and hysterical ideology. They deserve time to make decisions about their own bodies. Puberty blockers give them that time, and they do so safely and reversibly.

If you want to understand this better, have a look at the Endocrine Society’s guidelines. Read the WPATH Standards of Care. Look at the peer-reviewed evidence. It’s all there, and it all says the same thing.